Arrival in NZ

- bernienapp

- Jul 22, 2025

- 3 min read

“You will be taught the language, our money system, the rights and duties of citizenship, and our social customs before you attempt to make your way in communities throughout New Zealand.”

The words of the Immigration Minister, Hon A McLagan, on welcoming a shipload of refugees from eastern Europe into Wellington, on 27 June 1949, in a southerly gale. Our father and grandma were among more than 700 displaced persons from war who had taken ship 40 days earlier on the Dundalk Bay, in Trieste, Italy.

This was a port city swarming with desperate exiles leaving Europe. By this time dad (16) was making the decisions. How they got to Trieste we don’t know, other than a green light from the UN International Refugee Organisation to take ship to Argentina. They had heard of that. America was out of the question; the US were not taking mothers and children. So, the land of grilled steak, tango, and Eva Perón beckoned.

In all the turmoil, a ship heading for New Zealand docked first, and dad led Erika onto the Dundalk Bay; this old hulk was going somewhere, whereas who knew if any ship going to Argentina would ever arrive. Neither knew where or what New Zealand was. They spoke no English. Wearing only the clothes on their backs and carrying little else, this truly was adventure into the unknown.

The trip by ship saw grandma suffering from seasickness and confined to bed, while dad thrived. He would tell us stories of a big storm in the Indian Ocean, gaining a job as kitchen hand, and waving strips of greasy bacon from the galley window at passengers queuing for food on a plunging deck. Dad took the bacon. He gained weight during the voyage while others lost it.

Minister McLagan’s speech was among my grandma’s papers that trace in faded brushstrokes the long journey out of Estonia in 1944, ahead of Soviet invaders, and into Germany where they spent the next 5 years, moving from one refugee camp to another.

It’s a single sheet of foolscap, English on one side, with a translation into German for disembarking passengers on the other. The text reads as a warm welcome:

“Physical Welfare Officers will assist you to learn our sports and recreations so that you will be able to mix freely and enjoy life with New Zealanders. When you are ready to leave this camp the Department of Labour and Employment will find suitable jobs for you in various parts of the country. Where possible, friends will be found employment near one another.”

The other day I was tidying up and came across printed copies of newspaper clippings I’d collected at the National Library years before, covering the Dundalk Bay’s docking in Wellington. “Many victims of vicious regimes arrive to take up life in new land” ran one headline, in The Dominion of 28 June 1949.

The accounts of refugees arriving at the camp the Minister referred to, in Pahiatua, northern Wairarapa, told a story of relief. “It is clean,” one told a reporter. “First the camp in Italy, then the Dundalk Bay, which were both terrible. But now at last, we can believe what we are told.”

Dad recalled two months at Pahiatua, which he liked. In late August of that year he and Erika moved to Wellington where grandma found work as a matron at a university hostel, Weir House, up in the suburb of Kelburn. I can see the elegant old building from my city apartment.

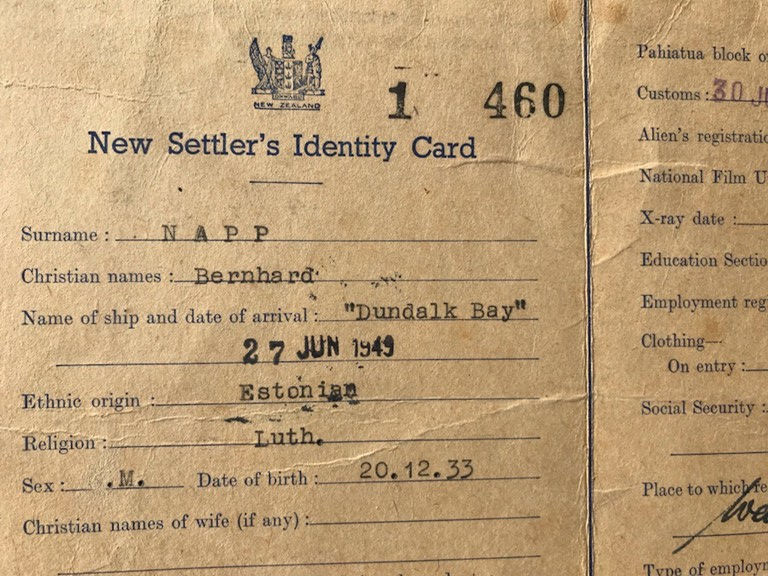

As stateless refugees, the arrivals each received a new settler’s identity card; dad’s read that he was Bernhard Napp, of Estonian ethnic origin, born on 20 December 1933, height, 5 feet 7 ½, colour of eyes, green. Some of this was wrong, as often occurred at the time. He attended secondary school, lasting less than a year; he thought it a childish waste of time. Compared to his unruly classmates, he was already a man, having survived five years of war, and another 4 in refugee camps, undernourished and on a constant hunt for food.

Our dad was nothing short of resourceful, in wartime and afterwards. In Wellington, he sold his collection of Hitler stamps to buy his mum a pair of shoes. On leaving school in early December 1949 he found work as a draftsman at the Post & Telegraph, through a contact he had made at Boy Scouts.

Studying by night, Bernard Napp eventually qualified as an architect, and he was launched – to find a wife through the ski club where he was something of a legend, build a house on a gorse and blackberry-covered hillside, father children, and later build a block of flats, to rent out and put grandma Erika on the bottom floor, alongside a workshop. A new life in a new land as the hopeful 1960s ran their course.

Comments